Who Was The First Person To Reach The North Pole Really?

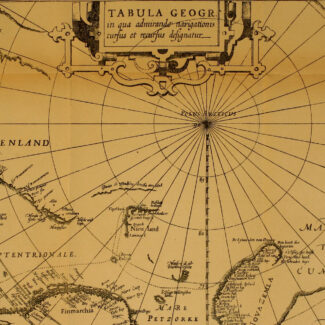

Among the more extreme points on Earth in more ways than one, both the North and the South poles were coveted prizes for explorers and adventurers, who vied—and sometimes died—for the honors of being the first to reach these frigid spots on the top and the bottom of the planet. We know for certain who left the inaugural footprints at the South Pole. But by contrast, the answer to “Who discovered the North Pole?” is an awful lot murkier.

Part of that reflects the very different environmental settings of the two poles. The South Pole has the “advantage,” from an explorer’s standpoint, of being located on land: set on the ice-buried bedrock of the Antarctic continent, to be specific. The North Pole, by contrast, is far from terra firma, cloaked in the ever-drifting sea ice of the Arctic Ocean. Set your flag at the South Pole, and it stays at that point; up at the North Pole, your flag starts inching away from the spot, riding the ice pack, as soon as you plant it.

We’ve prepared a whole article about the history and timeline of exploration centered on the North Pole, which you can read here. In this companion article of sorts, we’re specifically looking at who the first person to reach the North Pole was—and breaking down the convoluted contretemps between the two men to make that claim before any others.

Race to the North Pole: The Expeditions of Frederick A. Cook & Robert E. Peary

The greatest controversy concerning who reached the North Pole first has to do with the competing and much-contested claims of two Americans: Frederick A. Cook, a physician bitten by the exploration bug, and Robert E. Peary, a U.S. Navy civil engineer and well-known polar adventurer nearly a decade older than Cook who initiated numerous Arctic expeditions between 1886 and 1909.

Cook had volunteered on one of Peary’s Greenland trips in the early 1890s as expedition doctor (in which capacity he mended Peary’s broken leg at one point). These former comrades, however, would end up in conflict by the close of the first decade of the 20th century, when both made their own separate-but-overlapping shots at the North Pole.

Imagine the challenging terrain faced by Cook and Peary! This stark and beautiful Arctic vista hints at the treacherous conditions and the sheer determination required in the famous race to be the first to the North Pole.

Cook’s Account of North Pole Discovery

In the summer of 1907, Cook—who claimed to have submitted Denali (then called Mount McKinley), the highest mountain in North America, the year before—traveled to northwestern Greenland aboard the John R. Bradley, named for the expedition’s financial backer, who accompanied Cook to the outpost of Annoatok in order to hunt. The undertaking was ostensibly to study local Inuit culture, but, in Annoatok, Cook told Bradley he intended to try for the North Pole.

After months of preparation, Cook departed with an 11-dogsled-strong team almost entirely composed of Inuits in February 1908. As he’d planned, Cook sent team members back as they progressed along a route that had been proposed (though not attempted) by a Norwegian mapping expedition some years before. The final, Pole-bound party consisted merely of Cook and two Inuits, Ahwelah and Etukishook.

According to Cook’s account, he and his companions determined by sextant they’d reached the North Pole on April 2, 1908 and left a note in a brass rube there in the ice before leaving. Their return journey was harrowing, repeatedly obstructed by drifting ice and by open leads they crossed in a collapsible boat they’d packed along. Delayed, the three men were forced to overwinter in a cave on Devon Island in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago; they didn’t return to Annoatok until April 1909.

Peary’s Account of North Pole Discovery

Almost exactly a year later, on April 6, 1909, Robert Peary—who’d departed on his own expedition, the eighth and final one he’d make in the Arctic, from Greenland in August 1908, a fact Cook learned from American hunter Harry Whitney in Annoatok—would claim that he and his party reached the Pole.

That party—like Cook’s, drastically whittled down from the more than two dozen men and 100-plus sled dogs Peary embarked with—included four Inuit members and Matthew Henson, an African-American explorer who’d been on several polar expeditions with Peary.

Scouting in advance of the others, Henson was the first to reach the site of the party’s Camp Jessup, which Peary, the account goes, thereafter determined by sextant to be at the North Pole.

Before leaving Camp Jessup, Peary said he left a tin with a note and a piece of an American flag his wife had sewn at the site.

Words from the man himself? This is purportedly Robert Peary’s diary entry upon reaching the North Pole, offering a glimpse into his thoughts and feelings at the moment of his claimed achievement – a crucial piece of evidence in the ongoing debate.

Source: Robert Peary, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Dispute

Harry Whitney, the aforementioned American hunter, ended up embroiled in the high-profile rumpus that followed. Upon his return to Annoatok, Cook told Whitney of his achievement but asked he keep the news under wraps until Cook could make a formal announcement. Before beginning a long, circuitous journey back to New York that involved sledge travel and a sail to Copenhagen, Cook left several boxes of possessions—including his sextant and other equipment as well as most of the expedition’s records (save his polar diary)—with Whitney, who said he’d convey them later by ship.

The ship Whitney ended up catching to return back to the U.S. months later happened to be Peary’s expedition ship, the Roosevelt, on its return voyage. Via local word-of-mouth in Annoatok, an agitated Peary got wind of Cook’s claim to have gotten to the Pole in April the previous year—almost a full year before Peary allegedly did. Keeping his word to Cook, Whitney didn’t confirm or deny the rumor. Learning of Cook’s two Inuit companions, Peary brought Ahwelah and Etukishook aboard the Roosevelt and drilled them about their trip.

Crucially in this saga, Whitney claimed that Peary forbade him from bringing Cook’s boxes aboard, and so he had to leave them behind in a rock-set cache in Greenland.

Meanwhile, Cook’s Copenhagen-bound ship stopped in the Shetland Islands, from where, in early September 1909, he finally wired news of his achievement to the New York Herald. The Herald promptly ran a story under the headline, “The North Pole is Discovered by Dr. Frederick A. Cook.”

Hot on the heels of that announcement, on September 5th, Peary telegraphed the New York Times, a financial backer of his expedition, from Indian Harbour, Labrador, claiming he’d reached the Pole and casting doubt on Cook’s story.

And in the coming months, once both men had returned to the U.S., Peary and his patrons in the Peary Arctic Club intensified efforts to discredit Cook, whose account initially garnered plenty of public support.

Those efforts included questioning Cook’s purported summiting of Denali in 1906 (a claim that, over time, has come to be firmly rejected by the mountaineering community). Peary also published a transcript of his questioning of Ahwelah and Etukishook, whose responses and marked-out route on a map seemed to raise doubts about whether Cook’s party ever made it even close to the Pole.

Cook shared his diary with journalists in New York and announced more of his expedition records and his equipment—including the sextant he said he relied upon to confirm reaching the Pole—would be soon available for review. That was, however, before he learned from Whitney that Peary had refused to transport those belongings. Those boxes of Cook’s left behind in Greenland were never retrieved and, in fact, apparently never relocated at all.

Drawing from his diary, Cook wrote a report on his expedition and sent it to the University of Copenhagen, which released a skeptical assessment based on the scanty evidence and lack of real supporting materials.

By this point public opinion had largely swung over to Peary being the true first to reach the North Pole. Indeed, a committee appointed by the National Geographic Society, one of Peary’s sponsors, looked at his expedition records and deemed his claim credible.

To boost his claim further, in 1911, the U.S. House of Representatives subcommittee on naval affairs voted—albeit narrowly—to approve a bill giving him official recognition for his alleged North Pole exploits, having appeared before the body comprising many of his skeptics and shared his polar diary.

It should be noted, however, that according to an absorbing account in Smithsonian Magazine by Bruce Henderson (author of True North: Peary, Cook & the Race to the Pole—a highly recommended read), three members formally expressed “deep-rooted doubts” about his trip.

Another claimant to the crown! This image is associated with Frederick Cook’s 1909 Arctic expedition, adding another layer of complexity to the enduring question of who first conquered the North Pole.

Source: Frederick Cook’s expedition, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Assessing Cook’s & Peary’s Claims

The skepticism which met both Cook and Peary in the immediate wake of their announcements hasn’t gone away. The fact that Cook—who, later in life, ended up jailed for fraudulent activity in the oil industry—couldn’t produce much of any evidence besides his diary leaves his claim tenuous at best. The remarks and map markings made by Ahwelah and Etukishook at Peary’s request have led some to conclude that Cook’s party never were particularly close to reaching the North Pole. In his Smithsonian writeup, though, Bruce Henderson observes that Matthew Whitney, who could converse more fluently with Greenland’s indigenous peoples, reported that Cook’s two Inuit companions “told him they had been confused by the white men’s questions and did not understand the papers on which they were instructed to make marks.”

Disappointed by the Subcommittee on Naval Affairs’ only measured vote of confidence and resulting recognition, meanwhile, Peary never again shared his polar diary with outsiders and kept his navigational records under wraps. And questions about his party’s navigational techniques and prowess long remained the heart of the argument against his claim.

Peary claimed to have traveled to the pole using sun sightings without taking celestial longitudinal measurements. The other members of the team that reached Camp Jessup with him, Matthew Henson and the Inuit, were not trained navigators. The other navigator on Peary’s expedition, Bob Bartlett, was among the members sent back before the Pole was allegedly reached; skeptics have keyed into the unusually impressive leap in travel rate—from about 9½ miles per day to 26 miles per day—Peary reported after Bartlett’s departure.

Debate over Peary’s claim, which had continued over the decades since he made it, really flared up again in the late 1980s and early 1990s. With the permission of Peary’s family, the National Geographic Society invited a British Arctic adventurer, Wally Herbert—who himself journeyed to the North Pole by dogsled in 1969—to review Peary’s long-secret expedition records.

Herbert’s analysis, published in 1988 in National Geographic, cast strong doubt on Peary’s claim. Strong enough that the New York Times—like the National Geographic Society, a financial backer of Peary’s expedition—issued a correction to its original report from 1909.

As John Tierney summarized in a 2009 New York Times article, the National Geographic Society didn’t itself outright accept Herbert’s conclusion, and requested a report on the issue from a non-profit group called the Navigation Foundation.

That report, released in 1989 and widely covered in the popular press, appeared to validate Peary’s account. The Navigation Foundation concluded Peary’s sun-sighting method could indeed have steered the party 500-plus miles along true North, and judged that the murky expedition photographs they were given access to suggested a location within striking distance of the Pole.

But many criticized the Navigation Foundation’s work, not least its assessment of those photographs. And in 1993, Tierney reports, another hole was punched in the pro-Peary argument. Peary’s supporters had pointed to the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen allegedly successfully navigating to the South Pole (in December 1911) mainly by compass, without taking celestial measurements, as proof that Peary’s similar method could have worked to get him to the opposite pole. But a historian named Ted Heckathorn released evidence showing that Amundsen did in fact use celestial navigation on his Antarctic expedition.

The issue of whether Robert Peary made it to the North Pole in 1909 isn’t exactly settled. (The National Geographic Society, while duly reporting the controversy, has remained somewhat ambiguous as to its official stance.) But the consensus of many modern authorities is that he did not—but that he and his party likely did get quite close to the Pole, perhaps even within a few miles.

It’s worth emphasizing that, in the doubtful event that Peary did indeed establish his farthest-flung camp at the North Pole proper—and casting aside Cook’s mostly rejected bid for the honors—the first man on the North Pole by this account would be not even be Peary at all, but Matthew Henson. Indeed, Henson’s comment after scouting ahead on April 6, 1909—“I think I’m the first man to sit on top of the world”—apparently annoyed the rather vainglorious Peary.

In his account of the expedition, Henson noted Peary’s brooding mood on the return leg. That might have been a petty frustration that Henson had technically beaten Peary to the strived-for landmark. It could also have been a reflection, as some have suggested, of Peary’s own doubts about whether the party had actually attained the North Pole in the first place.

The iconic image! This is the scene Robert Peary claimed to have witnessed at the North Pole with his team and flags – a moment of alleged triumph that remains at the heart of a century-old dispute about who truly reached the top of the world first.

Source: National Archives at College Park, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

So—Who Discovered the North Pole?

It’s probably safe to say that the majority of experts today dismiss both Cook’s and Peary’s claims as being the first to reach the North Pole—though more than a few supporters of both remain vocal in their convictions.

If not those two competing Americans, who, then, can we definitely award the laurels? In fact, the next round of contenders comes with another round of controversy. Polar explorer and U.S. Naval officer Richard Byrd claimed to have flown over the North Pole, along with Floyd Bennett, on May 9, 1926, in the airplane Josephine Ford. Only three days later—and departing, like Byrd and Bennett, from Spitsbergen—Roald Amundsen and his crew passed over the Pole aboard an airship, the Norge.

Byrd’s account came under much skepticism due to questionable records and inconsistencies. The Norge’s overflight of the North Pole, by contrast, is undisputed. Therefore, in terms of the first absolutely definitive visit to the North Pole, it’s Amundsen and his crew (among them Lincoln Ellsworth, who, like Amundsen and Byrd, is also well known in the annals of history for his Antarctic explorations) who get the crown, making him the conqueror of both poles.

But what about setting foot at the North Pole? If we are to disregard both Cook and Peary—and by extension Henson—the first documented footfalls at the North Pole were actually those of a Soviet research group led by Aleksandr Kuznetsov. The scientists were flown to the Pole on April 23, 1948 for several days of data collection. (If you were to discount flying, the first group to definitively reach the North Pole over the ice was a team led by Ralph Plaisted of the U.S., who did so via snowmobile on April 20, 1968.)

Today, amazingly, visiting the North Pole is possible not only by airplanes, snowmobiles, and dogsleds, but also on an expedition cruise by ice-breaker. Will you be next to follow in the footsteps of Cook, Peary, Henson, and others to achieve this incredible feat and embark on a North Pole cruise?

Disclaimer

Our travel guides are for informational purposes only. While we aim to provide accurate and up-to-date information, Antarctica Cruises makes no representations as to the accuracy or completeness of any information in our guides or found by following any link on this site.

Antarctica Cruises cannot and will not accept responsibility for any omissions or inaccuracies, or for any consequences arising therefrom, including any losses, injuries, or damages resulting from the display or use of this information.